Individualized Care Plans for Acute Sickle Cell Pain Crises

February 2020

If you would like to view the videos from this event, please click the links below.

Video 1

Video 2

Vignette

Mr. J. is a 22 year old male presenting to your urban emergency department complaining of his typical sickle cell pain in his knees, back, and shoulders for the last 2-days. he reports no recent viral of febrile illness, blunt trauma, travel history, or sock contacts. His home pain medications have been ineffective and he notes not recent change in his doses. He denies recent alcohol use or any history of intravenous or illicit substance abuse – and his Opioid Risk Tool screen is low risk for substance use disorder. He has been to your ED about 4-times per year over the last few years and always for sickle cell pain crises.

In the ED, his vital signs are BP 120/70, P 58, RR 18, T 37.0°C, and 100% oxygen

saturation on room air. No objective evidence of acute intoxication or trauma are

appreciated. He appears extremely uncomfortable and you note that he has been waiting

in triage for 6-hours due to ED crowding.

Yesterday, you received separate emails from the American College of Emergency

Physician’s and the American Medical Association highlighting the role of physician

prescribing in the ongoing opioid epidemic. Both emails encouraged physicians to

prescribe less opioids and you remember a recent Missouri Medicine series with the same

message. You are also aware of National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI)

guidelines endorsing initial analgesia within 30-minutes of triage based on individualized

care plans. Seeking to balance the overriding cry for opioid stewardship with the time-dependent urgency of NHLBI-guided sickle cell analgesia, you seek to find and critically

appraise the evidence underlying the guidelines.

PICO Question

Population: Adults with confirmed sickle cell anemia in the ED with acute pain crisis.

Intervention: Initial opioid dosing based on individualized care plan and within the timeframe endorsed by NHLBI guidelines

Comparison: Standard ED pain management

Outcome: Proportion with pain relief within 1 hour, Ed length of stay, hospital admission rate, ED returns within 72 hours, adverse medication events (apnea, hypotension, hypoxia)

Search Strategy

Initially, you review the NHLBI Guideline (specifically Chapter 3 on Managing Acute

Complications of Sickle Cell Disease). Unfortunately, you find no references for the

recommendations endorsing individualized care plans. Therefore, using this PICO question, you devise a PubMed search using Clinical Queries (therapy/broad) and the

search term “sickle cell pain crisis” which identifies 329 studies (see https://tinyurl.com/

yxjrcuve) from which you identify Tanabe’s 2018 randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Your search yields no additional RCT’s so you reluctantly expand your criteria to include pediatric and observational studies, which yields the remainder of these studies from your

original search strategy.

Articles

Article 1: A randomized controlled trial comparing two caso-occlusive episode (VOE) protocols in sickle cell disease, Am H Hematol 2018; 93: 159-168 ANSWER KEY

Article 2:Impact of individualized pain plain on the emergency management of children with sickle cell disease, Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014; 61: 1747-1753 ANSWER KEY

Article 3: Timing of opioid administration as a quality indicator for pain crises in sickle cell disease, Pediatrics 2015; 135: 475-482 ANSWER KEY

Article 4: Safety of an ED high-dose opioid protocol for sickle cell disease pain, J Emerg Nurs 2015; 41:227-235 ANSWER KEY

Bottom Line

Sickle Cell Vasocclusive Pain Crises – A Medical Emergency Sickle cell disease (SCD) affects about 100,000 Americans. Each year, more than 230,000 emergency department (ED) visits occur in the United States for SCD-related vaso-occlusive episodes (VOE) of pain, accounting for over $1.5 billion in health care expenditures. SCD patients’ Hematologists often prescribe SCD patients chronic opioids and acute VOE usually require opioids for effective pain relief. Intravenous opioids have been the standard ED management for acute VOE for over 40-years, although not without some disagreement. This reality exists in an era when ED physicians operate under the microscope of the 21st Century’s opioid epidemic. High rates of ED returns occur in a small proportion of SCD patients and may bias emergency medicine physicians’

perceptions of pain, empathy, and degree of patient-physician trust (Elander 1996,

Haywood 2009, Haywood 2010, Carroll 2011). Indeed, negative attitudes towards SCD

are associated with lower adherence to VOE pain management guidelines, although the

majority of ED physicians report adherence to these recommendations. Some experts also

question whether the level of monitoring SCD VOE patients in ED settings after receiving high-dose opioids. A 2019 Cochrane review of pharmacological therapies for SCD pain crises identified only nine studies and concluded “the available evidence is very uncertain regarding the efficacy or harm from pharmacological interventions used to

treat pain”.

These issues undoubtedly negatively affect the experience of care for many SCD patients’

ED visits for VOE pain crises – and lead to disparities in care. On average, adult SCD patients with VOE pain wait longer to see a physician than those with a long bone fracture. In addition, renal colic patients receive opioid therapy 30-minutes faster than SCD patients do. When painful stimuli present to peripheral sensory neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord accentuates (current and future) pain.

The Response – Guidelines & Preliminary Implementation Strategies

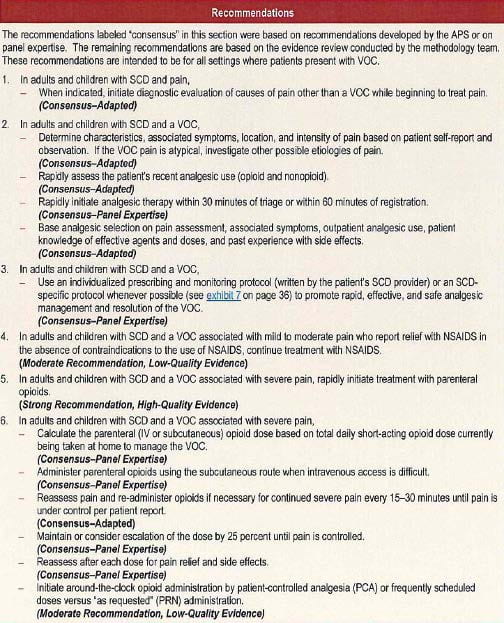

In response to the barriers to prompt SCD VOE analgesia in EDs nationwide, SCD

patient advocates and Hematologists created the National Heart Lung and Blood

“Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease” guidelines in 2014. As depicted

in Figure1, these recommendations include creation of an individualized prescribing

protocol written by the patient’s SCD provider, as well as rapid parenteral opioid therapy

with re-assessment every 15-30 minutes until pain is controlled. Notably, all of these

recommendations are consensus-based rather than derived from high-quality randomized

controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews.

FIGURE 1 – Synthesis of NHLBI SCD Pain Management Guidelines (2014)

Concurrently, the American College of Emergency Physicians launched the Emergency

Department Sickle Cell Care Coalition (EDSC3). EDSC3 exists to disseminate SCD research findings, educate ED teams regarding SCD-related pain and other complications, develop health care performance metrics, support community outreach, and provide advocacy efforts. The ACEP EDSC3 website includes links to multiple resources to support these objectives. In 2015, NHLBI funded a large multi-institutional, transdisciplinary grant to use implementation science in optimizing adolescent and adult SCD management and align ED care with – including VOE pain crises. This Journal Club is part of that NHLBI U01 award with the intention to critically appraise existing evidence that benefits outweigh harms for individualized patient care plans and/or strict adherence to the prompt opioid therapy recommended.

Journal Club Discussion Between Hematology & Emergency Medicine

Here is the synopsis of the Journal Club discussion between Hematology and Emergency

Medicine, including Dr. Allison King and Dr. Sana Saif Ur Rehman.

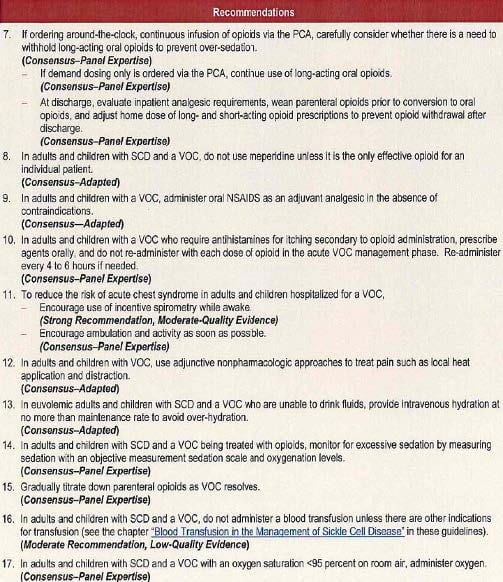

There was agreement that adult sickle cell pain acutely in the ED can be frustrating for

patients and the emergency medicine health care team. ED crowding lengthening typical

waiting room times beyond the NHLBI Guideline 30-minute window for initial parental

opioid represents the most prominent challenge. In reviewing the NHLBI Guidelines

above based almost entirely upon consensus, the lack of high-quality evidence prior to

the Guidelines was also acknowledged as a “leak” in the Knowledge Translation Pipeline

(see below) – primarily in “acceptance”. Another KT leak threatening “applicability”

was the problem of SCD patients “fired” from Sickle Cell Clinic. Attending clinic saves

money and reduces ED visits (Yang 1995). Hematology and EM agreed that SCD

patients cannot and will not be “fired” from Sickle Cell Clinic so that every local patient

has the opportunity to develop an individualized care plan with their Hematologist. In

addition, after a brief discussion attendees agreed that inclusion of a uniform opioid use

disorder screen for all ED patients prescribed opioids (including SCD) as a component of

the individualized care plan would be additive.

FIGURE 2 – Knowledge Translation Pipeline

Critical Appraisal Synopsis (see Answer Keys for more details)

PGY-I

A two-center RCT demonstrating multiple benefits favoring patient-specific protocols for

acute analgesia in SCD VOE pain crises, including overall pain relief and reduction in

opioid side effects. However, a concerning (non-significant) signal noted for increased

rates of ED revisits and hospitalizations within 3-days for patient-specific protocols. In

addition, 1/3 of patients declined enrollment at the outset, which may indicate patient

reluctance to initially accept or adhere to patient-specific plans in real-world settings.

Additional pragmatic randomized controlled trials limiting exclusion criteria and using

actual non-research providers to re-assess pain/side effects would substantially enhance

the external validity of these findings, if such studies reproduced the benefits and lack of

harms.

PGY-II

This study demonstrates one institutions’ innovation in creating individual care plans

prior to the 2014 NHLBI guidelines, but multiple design and reporting flaws limit our

ability to confidently extract knowledge from this observational data. Quality

improvement teams and future researchers can learn from the methodological and

reporting flaws that limit readers’ ability to reproduce this innovation or to ascribe these

care plan to improved patient outcomes confidently.

PGY-III

Imperfect single-center chart review which demonstrates no significant reduction in

pediatric sickle cell patient admission rates associated with time to parenteral opioid

administration in the emergency department. Secondary outcomes suggest a significant

trend towards more rapid pain relief, reduced ED length of stay, and higher total dose of

ED opioid prescribed. However, multiple limitations noted raise concerns about the

reproducibility and accuracy of these results in different time periods or pediatric

hospitals. In addition, extrapolation of these results to adult SCD VOC patients with

generally longer waiting room times and ED length of stay should be done cautiously.

PGY-IV

This was a low-quality chart review study demonstrating no adverse respiratory events

associated with higher morphine-equivalent opioid doses associated with SCD VOE pain

crisis management in one urban academic ED. These results provide weak evidence of

safety for VOE pain protocols using higher opioid doses.

Future Research Priorities

1. The PGY-I manuscript provides higher quality evidence of efficacy (an

intervention that “works” in ideal study settings). Pragmatic studies that replicate the

safety and effectiveness of individualized patient care plans with appropriate dosing

of opioids in adult sickle cell patients are still needed. Pragmatic studies occur

without research assistants and minimize exclusion criteria to mirror clinical

operations in the fast-paced, less academic ED and hospital settings including rural

sites without a hematologist, emergency physician, or electronic medical record.

2. Alternatives to ED SCD. Sickle Cell Day Clinics exist at other institutions and

provide a viable alternative to the ED for some patients on some days. In children,

these “Day Clinics” reduce length of stay and decreases hospital admission rates in

adults (Wright 2004, Gowhari 2015, Han 2018). Barnes Jewish Hospital has a Sickle

Cell Quality Committee co-led by Hilary Harris and Angelleen Peters-Lewis. In

conjunction with Dr. Sana Saif Rehman, building and sustaining a Sickle Cell Day

Clinic at Barnes Jewish Hospital is a priority.

3. Additions to ED SCD Analgesic Protocols. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is

routine once SCD patients are admitted to the hospital, yet remain off-limits for ED

providers struggling to manage sickle cell pain for hours to days among boarding

patients. Inpatient PCA pumps reduce hospital length of stay (van Beers 2007). ED

PCA appears safe and effective for traumatic and non-traumatic abdominal pain and

multiple etiology pain, yet may remains unavailable at Barnes Jewish Hospital.

Defining the barriers and nurse/physician acceptable safety thresholds to introduce

PCA could be additive to SCD individualized care plans for admitted patients and

ease ED crowding downstream by reducing hospital length of stay.

4. Emerging preventative therapies. Crizanlizumab is the first FDA approved drug

to reduce the frequency of SCD pain crises. This non-narcotic therapy is a one-month

infusion that targets the pathophysiology of SCD pain crises by antagonizing an

adhesion molecule expressed on red blood cells and endothelial cells. In explaining

this to non-medical folks, crizanlizumab creates slippery that glide through blood

vessels regardless of sickling, thereby avoiding clumping and vaso-occlusive

hypoperfusion.

5. Implementation Science. Although the NHLBI grant funding this multiinstitutional

project is an implementation science award, none of the studies identified

report implementation science approaches. This study (and other similar ED-based

sickle cell pain crisis interventions) can and should adhere to StaRI reporting

standards by reproducibly evaluating and reporting

- Cultural capacity to adapt to higher dose initial morphine equivalent dosing in the midst of an opioid epidemic (context into which the trategy is being implemented);

- Prescribing biases at the level of patients/family/nurses/physicians;

- Resource “costs”, and

- Fidelity of multiple components (the individualized care plan development

between patient/hematologist, education of ED nurse/physician about individualized

plan rationale, incorporation of individualized plan into electronic medical record,

and communication/adherence of that individualized plan between patient and

provider during an episode of ED care.

6. Adherence to StaRI in emergency medicine optimizes implementation

investigators’ capacity to differentiate problems with the intervention from problems

with the implementation strategy, if the hypothetical benefits are not attained. The

NIH developed a framework of these implementation measures in 2015.

7. Guideline concordance. The NHLBI Guidelines form the basis of this project and

Journal Club, but the American College of Emergency Physician’s also have an

opioid prescribing clinical policy. The ACEP Clinical Policy does not contemplate

SCD vaso-occlusive crises as a unique population, nor does the NHLBI Guideline

acknowledge the ACEP Clinical Policy. In the future, one cohesive guideline from

NHLBI and ACEP would serve to accelerate knowledge translation, but will require

compromise and coordination.

Summary: Despite a paltry evidence basis, the combination of known disparities in

analgesia, guideline consensus and SCD patient experience favor accepting

individualized care plans for timely and appropriate ED analgesia – while continuing to

re-evaluate safety and efficacy.