Washington University Emergency Medicine Journal Club – November 2025

Dr. Brian Cohn

Hello all,

Thanks to all who attended the November Journal Club on dual/double defibrillation for refractory ventricular fibrillation. Please see the Bottom Line below and the attached answer keys and full write-up. See you in January…

Vignette

You’re working a busy TCC shift one weekend when you get a page that EMS is bringing

in a 50s-year-old man in cardiac arrest. You prep the room and discuss the plan with the

team, emphasizing high-quality CPR with minimal interruptions.

The patient arrives with a King tube in place, in ventricular fibrillation. EMS reports the

patient was in V-fib on their arrival about 15 minutes earlier. They have attempted

defibrillation twice, have given three rounds of epinephrine, and have given 150 mg of

amiodarone, all with no change in rhythm. You immediately attempt defibrillation for a

third time, with no change in the patient’s condition, and give an additional 150 mg of

amiodarone. Two minutes later, the patient remains in v-fib.

When the patient remains in v-fib after two additional attempts, you and the attending

exchange a, “Well, what now?” look. You begin to wonder if there are additional

medications or maneuvers for patients in refractory V-fib. You later begin searching for

answers online, and stumble upon a write-up from REBEL EM (https://rebelem.com/

defibrillation-strategies/) on this very topic in which the authors reviewed a prior study on

dual sequential defibrillation. Being wary of other’s opinions, and being adept at

appraising the medical literature yourself, you perform your own literature search and

begin evaluation the evidence on your own.

PICO Questions

Population: Adult patients with refractory ventricular fibrillation

Intervention: Dual defibrillation (sequential or simultaneous)

Comparison: Standard ACLS/defibrillation

Outcome: ROSC, survival to hospital admission, survival to discharge, and

neurologically intact survival

Article 1: Cortez E, Krebs W, Davis J, Keseg DP, Panchal AR. Use of double sequential

external defibrillation for refractory ventricular fibrillation during out-of-hospital

cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016 Nov;108:82-86. [Answer Key].

Article 2: Ross EM, Redman TT, Harper SA, Mapp JG, Wampler DA, Miramontes DA.

Dual defibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A retrospective cohort analysis.

Resuscitation. 2016 Sep;106:14-7. [Answer Key].

Article 3: Cheskes S, Verbeek PR, Drennan IR, McLeod SL, Turner L, Pinto R,

Feldman M, Davis M, Vaillancourt C, Morrison LJ, Dorian P, Scales DC. Defibrillation

Strategies for Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2022 Nov

24;387(21):1947-1956. [Answer Key].

Article 4: Yu J, Yu Y, Liang H, Zhang Y, Yuan D, Sun T, Li Y, Gao Y. Defibrillation

strategies for patients with refractory ventricular fibrillation: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2024 Oct;84:149-157. [Answer Key].

Bottom Line

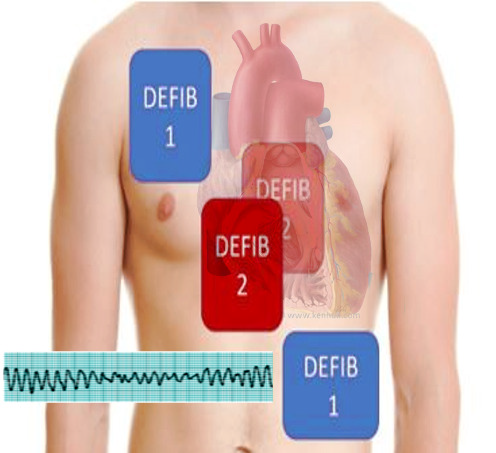

The mainstay of treatment for patients who present in ventricular fibrillation (VF) includes high-quality CPR, rapid defibrillation, and the administration of antiarrhythmia medications such as amiodarone or lidocaine. For patients who remain in VF despite these efforts, dual sequential (or double sequential) defibrillation (DSD) has been proposed as a method to increase the energy administered during defibrillation and thereby increase the probability of successful conversion to sinus rhythm. The procedure involves the placement of 2 sets of defibrillation pads, one placed in standard positioning, and a second set in the anterior/posterior position (see image and video). While DSD remains controversial, it’s use as a last-ditch effort to restore circulation in patients for whom standard management of VF has failed has shown promise in recent research.

In 2016, an early case series of 12 patients with refractory VF despite 5 single defibrillation attempts found that ROSC was achieved in 3 patients (25%, 95% CI 9% to 53%), all of whom survived to hospital discharge. The discharge Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) score was 1 in 2 of the patients and was 3 in the third, meaning that discharge with a good neurologic outcome occurred in 17% (95% CI 5% to 45%) of cases. No harm was demonstrated in any of these cases.

A retrospective cohort analysis published in the same year identified 279 cases of VF refractory to three attempts at standard defibrillation. Of these, 50 were treated with DSD and 229 with further standard defibrillation. This study demonstrated no significant difference in rates of ROSC (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.33-1.27), survival to hospital admission (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.45-1.65), survival to hospital discharge (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.17-1.53), or survival with a good neurologic outcome (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.15-1.72). The primary limitation of this retrospective review was selection bias and a resulting imbalance in key confounders between groups. Specifically, patients in the control group were more likely to have the arrest witnessed compared to the DSD group (54.6% vs. 38.0%) and more likely to receive bystander CPR (45.4% vs. 30%), both of which are known predictors of survival from OHCA (Sasson 2010). It is possibly that any benefit from DSD was missed as this group started out at a significant disadvantage.

More recently, a cluster-randomized controlled trial with crossover was conducted in six paramedic services in Ontario, Canada between March 2018 through May 2022 (Cheskes 2022). A total of 405 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and refractory ventricular fibrillation of presumed cardiac cause were randomized to standard defibrillation (n = 136), vector change (VC) defibrillation (n = 144), or double sequential external defibrillation (DSED) (n = 125). Survival to hospital discharge occurred more frequently in the DSED group compared to the standard group (RR 2.21; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.67) and in the VC group compared to the standard group (RR 1.71; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.88). Similar improvements were seen for termination of VF. Return of spontaneous circulation occurred more frequently in the DSED group compared to the standard group (RR 1.72; 95% CI, 1.22 to 2.42) with a statistically nonsignificant trend toward improvement in the VC group (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.99). Similarly survival with a good neurologic outcome occurred more frequently in the DSED group (RR 2.21; 95% CI, 1.26 to 3.88) with a less-pronounced statistically nonsignificant trend toward improvement in the VC group (RR 1.48; 95% CI, 0.81 to 2.71).

A recent meta-analysis pooled the results of five observational cohort studies including 1360 patients with refractory VF. Of these, 359 were treated with dual defibrillation and 1001 were treated with standard defibrillation (Yu 2024). Pooled results demonstrated no significant difference in rates of ROSC (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.59–1.02) or survival to hospital discharge (RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.46–1.78). There was also no significant difference in rates of survival to hospital admission or survival with a good neurologic outcome.

While the bulk of evidence, including a meta-analysis of 5 studies, demonstrates no improvement in outcomes with the use of dual defibrillation (sequential or simultaneous) for refractory ventricular fibrillation, all of the negative studies were retrospective and observational in nature. By contrast, the single cluster randomized controlled trial demonstrated fairly significant improvement in all outcomes with DSED. The hierarchy of evidence would suggest that this large, more methodologically robust trial supersedes the results of these non-randomized studies. Given that there is no known harm from the use of dual defibrillation, and the lack of response from all other treatments in the patients—including standard defibrillation and anti-dysrhythmic administration—it seems reasonable to attempt dual defibrillation in cases of refractory VF.